Some addicts we love...

...and--despite our best efforts at forgiveness--some addicts we loathe.

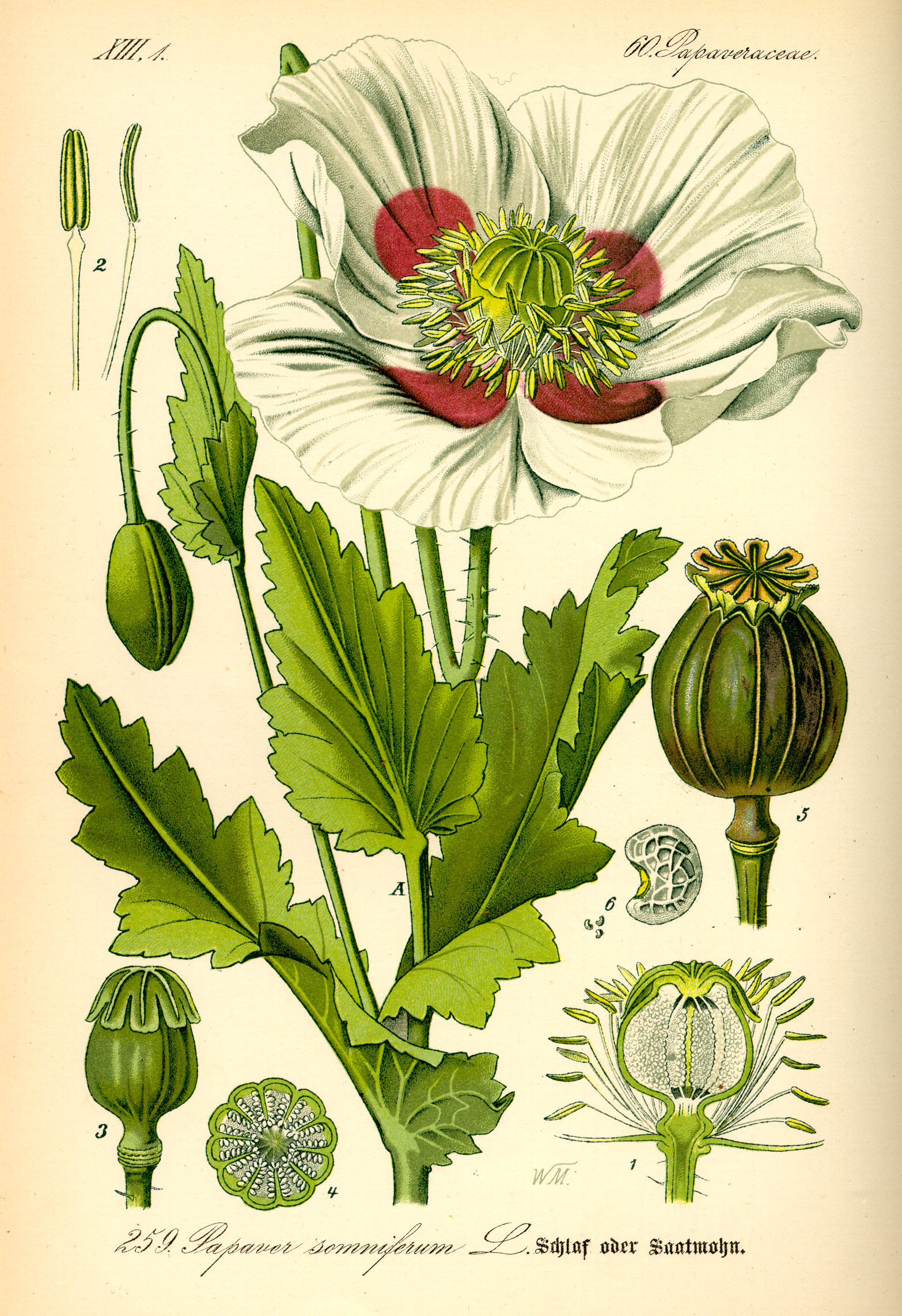

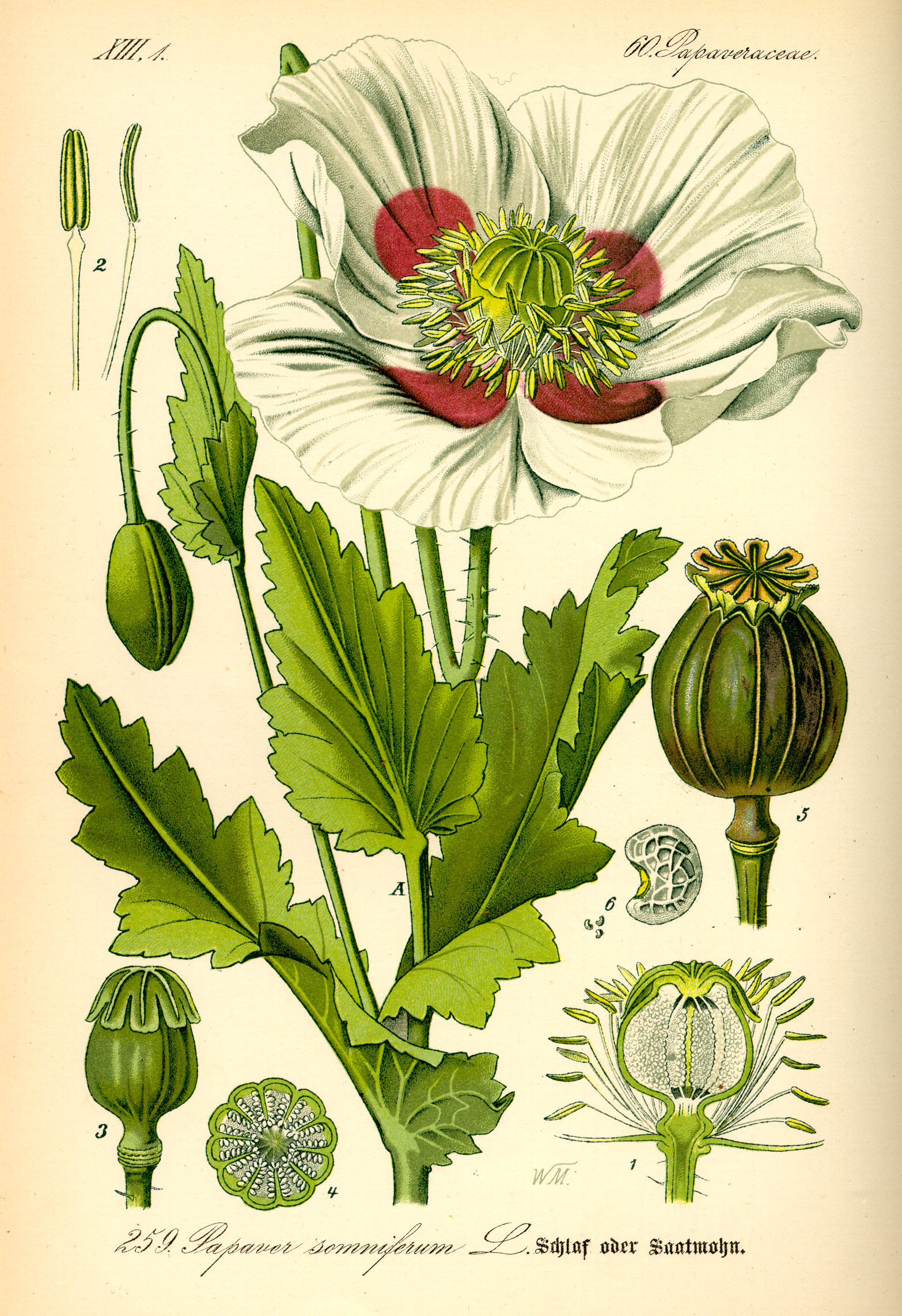

photos: Andre Royo as "Bubbles" from HBO's The Wire; Rush Limbaugh in his booking photo from the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office in April 2006, from Wikimedia Commons; below, Papaver somniferum from Wikimedia Commons.

Sometimes I prescribe medicine; sometimes I prescribe drugs. Prescribing drugs is much more difficult.

The Drug Enforcement Agency gives every doctor a number, which allows tracking of prescriptions for "controlled substances"--in other words, medicine that can double up as what we more often call "drugs", i.e., the stuff that can get you high. Because I'm an intern, my DEA number only works when I'm working for my hospital; but it works nonetheless.

I am reminded every day of the distinction between medicines that can't get people high and medicines that can. I print up pages of prescriptions when discharging patients, and then go through them and--pulling out my DEA number from its concealed spot on my person--write out the number for the controlled substances.

Going through the list, I know that this one is an antibiotic that could send someone into anaphylactic shock, but it doesn't get my DEA number; this other one could destroy someone's kidneys, but it doesn't get my DEA number either. These medicines can be dangerous, but they're just medicine. They're controlled by professional self-regulation, and ordinary prescription and medical licensing laws.

But this prescription is for an "anti-anxiety medicine." It can roughly be thought of as vodka in a pill, and it does get my DEA number. And this one to treat pain--I only write for the exact number of pills required to get the patient to her next primary care appointment--is basically heroin in tablet form. These medicines are "controlled" in a different way. These are the medicines that the apparatus of the state won't just entrust to the good intentions and professional pride of doctors. If we write bad prescriptions for medicines, we can lose our medical licenses. But if we write too many prescriptions for "drugs"--for the controlled substances--we can be charged and imprisoned.

Though various drugs fit into the category of "controlled substances", it's the opiates--the variations on the chemical structure of the opium poppy--that cause interns the most trouble.

There are a lot of people who have pain serious enough to require intensive medical therapy, so we need to prescribe opiates fairly frequently. But there is also a whole class of people out there who are addicted to prescription drugs, the Rush Limbaughs of the world.

The two sets of people overlap considerably, so drawing a line between the "good" opiate-takers and the "bad" ones is as impossible as it is morally dubious. Even for someone who has no pain, the way to feed the addiction is to create the appearance of pain when coming into the room for the doctor's visit. And what is more subjective than pain? Who am I to say you don't have pain, when you say that you do?

This is where interns come in. Most of us start getting resentful early, because the structure of academic medical clinics means that people looking for prescription opiates are often looking for us. First of all, we look like easy marks; we maybe haven't seen every scam a dozen times yet. Also, we're the ones who are accepting new patients and have plenty of new patient appointment slots to fill. That's perfect for "doctor shopping", which is how some people try to get either the single doctor who prescribes the most opiates, or a bunch of simultaneous legitimate prescriptions for the same opiate medicine.

In the hospital, we're the doctors who actually write the orders; who see the patients most often; who get paged first when the patient hits the nurse call button again and again demanding to see the doctor. (If there's anyone in the hospital who gets more enraged and embittered by prescription drug addiction than interns, it's nurses, who spend exponentially more time than we do responding to requests for pain medicine.) So we have a lot of contact with people asking for opiate medicines.

The majority of the time they're asking for those medicines because whatever put them in the hospital hurts, a lot. Sometimes, though, we're not sure how much of what drives the request is pain and how much is craving. Or we're frankly pretty sure they're trying to feed cravings we don't want to satisfy. How we diagnose this formally is hard to say, exactly, but our gut feelings are unmistakable. In our workroom the other day, a colleague of mine said, "Sometimes you just want to give the diagnosis of FOS"--Full Of Shit.

I actually like caring for heroin addicts who are open about their use. I hope they kick the habit. But if they don't, I'm fine with talking about clean needles, getting tested for hepatitis, and avoiding skin infections. I'll look for endocarditis, send out HIV antibody tests, keep an eye out for toxic exposures from drug contaminants, and work the phone for liver clinic follow-up appointments. I'll even sit and listen to self-pity for a while, because maybe within some of the self-pity will come the realization of hitting bottom. And that's an opening for change.

Within all of this--much of which is difficult, and some of which sometimes involves some scams and silences and lies--at least the patient and I are both talking about heroin for what it is. It's an addictive substance that gives both pleasure and relief, and also carries risks and problems. It's a substance that someone is taking of their own volition, and isn't asking me to prescribe.

But much as I'd like to be the humanistic doctor who isn't bothered by what bothers other doctors, I have to say that prescription drug addicts do stretch me to my limits of forgiveness. They need me to prescribe them their addiction, in a cleaned-up denial-inducing form. And they inspire doubt in me even in my clearest moments, because I don't want to leave pain untreated. They know that my doubt is an opening, an emotional wedge.

I want to avoid being manipulated by people with hidden agendas. But I can't simply turn off my capacity for worrying about pain. How do I know at the beginning of a clinic visit that my empathy is not a human gesture, but merely the potential key to the DEA-regulated lockbox? And when someone says to me that I am not successfully treating their pain, how can I possibly know for sure when they're lying to me? (We do have some tricks up our sleeves to try to figure this out, but their reliability is somewhere from uncertain to quite low.)

At the end of an interaction with someone I think has crossed the line from complicated pain treatment into simple drug addiction, it is almost impossible to feel proud, or good at my job. And it is impossible not to feel a little abused.

I am not laboring under the illusion that by withholding or limiting prescriptions for opiates, I'm curing addiction. Far from it. I know that the pharmacy of the street contains every drug that the chain-store pharmacy carries, and more. If someone wants this stuff, they can get it. But I don't want to put a clean white coat over someone's addiction. I don't want my training to become someone else's denial. And if I'm not curing addiction by holding back on certain prescriptions, at least I'm not feeding it.

The problem with this is obvious. It's for all of these reasons, and more, that much of chronic pain does go undertreated in the United States. The prejudices that get layered onto this struggle also mean that an unemployed black man with a lot of back pain is probably less likely to get his pain treated than an employed white man with much less back pain. At the same time, it's simplistic to say that everyone who rates their pain as "10 out of 10" should get their opiate dose doubled as some kind of democratic principle.

I spent a lot of time in medical school thinking about what it meant to be a democratic doctor. In my ideal world, I am a doctor who acts as a consultant to people who are trying to manage their own health. I am not taking care of people; I am helping people take care of themselves.

But every democracy has its vulnerabilities, its way of being subverted by anti-democrats. Every democracy depends on a predominance of good intentions, and so too does the democratic clinic. Prescription opiates are where the democracy in my clinic is most tested, and where I most commonly fall short of my ideals. My eyes narrowed and my heart suspicious, my hands grip the lock firmly; I will let no one else open the box. My DEA number is mine, and mine alone.

When it comes to opiates, my democratic clinic is constantly at risk for becoming a failed state. Generally my clinic muddles along more or less as it is supposed to. The trains don't run on time, but they run. But with opiates, the slightest difficulty provokes an untenable choice between a chaotic ungoverned world of individual self-interest, and iron-fisted dictatorship.

The opium poppy: you say you want it for the receptors in your central nervous system, but is it really for the hunger in your heart?

The opium poppy: you say you want it for the receptors in your central nervous system, but is it really for the hunger in your heart?